Over a millennia before Homer’s Odysseus followed Ursa Major home from Troy, the Minoans of Crete were already sailing by the stars. According to a new study, Bronze Age Minoans used celestial navigation techniques similar to the Polynesians, despite living over 17,800 km and around thousands of years apart.

The Minoans flourished on the Greek island of Crete in 2,600–1,100 BCE and are considered the first European civilization. Crete quickly became a place of immense wealth (which was consolidated in the hands of the elites) and specialized in trade with the Near East and Egypt. Access to the gold, ivory, and tin that the Minoans craved required advanced sailing techniques.

The recent findings have shown that the technique of using star paths to navigate the seas emerged much earlier than previously thought. Ancient Minoan traders, and possibly even the legendary navy of King Minos (thought to be the world’s first professional navy), used the rising of key stars to transverse the Aegean and Mediterranean seas.

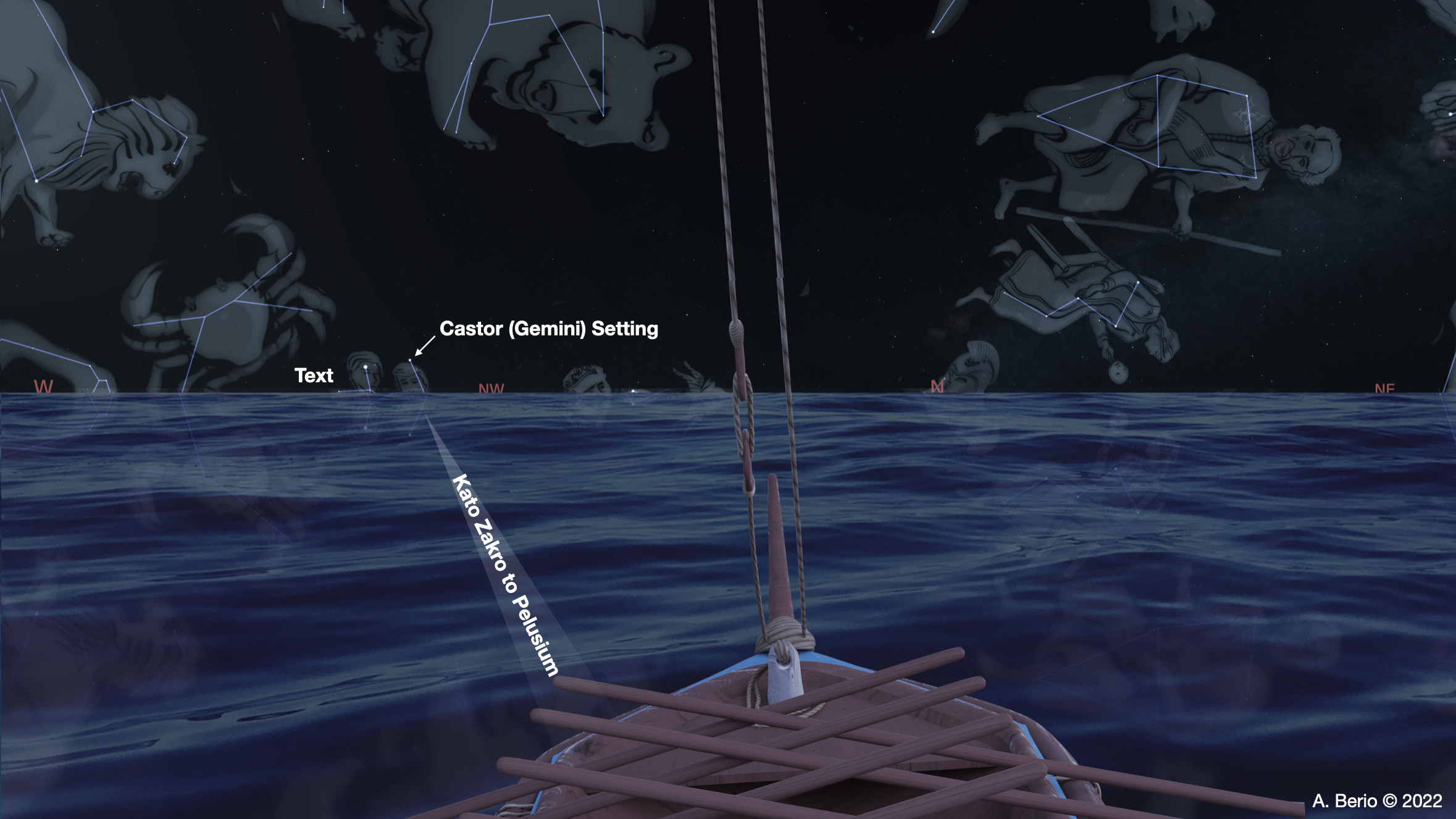

A simulated example of a star path.

Minoan palaces and the stars of the east

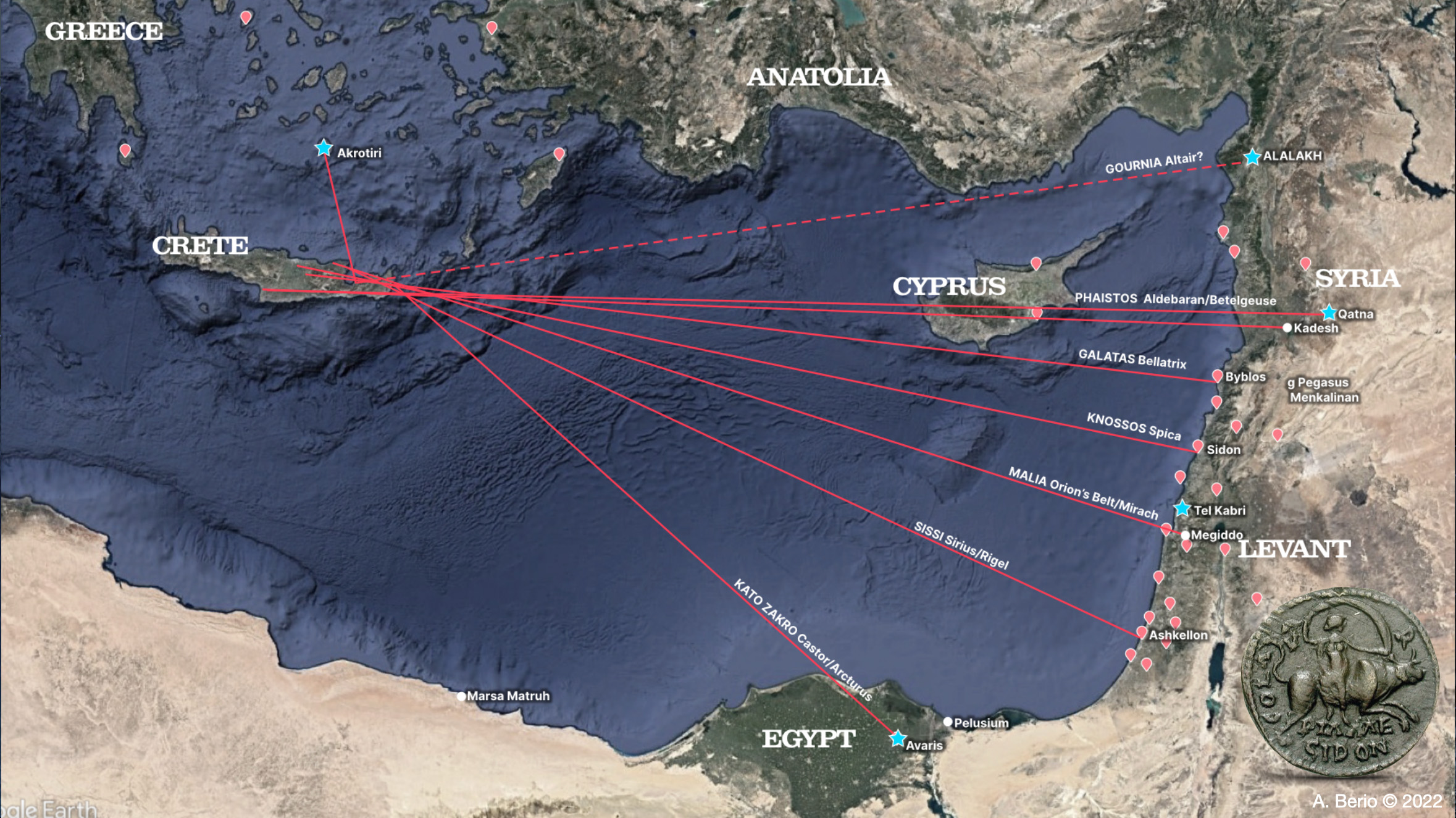

The many grand palaces built on Crete by the Minoans point to the importance of international trade. These palaces, including those at Knossos, Kato Zakro, and five other locations, were orientated towards trading partners to the east and south and towards the navigational stars that would take them there. Wealthy Minoans looked out upon famous bright stars, like Sirius, Orion’s Belt, and Spica. As these stars rose to the horizon, they could be used to direct open sea navigators to the east.

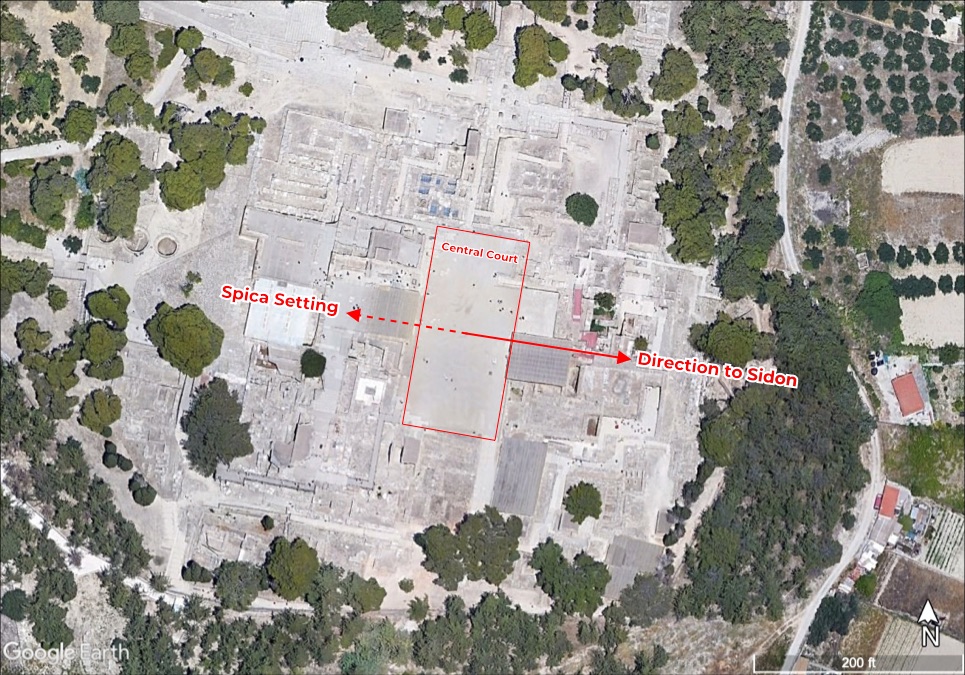

360° view of Kato Zakro Minoan palace central court with orientations toward the navigational stars and direct route toward Egypt.

360° simulation on a minoan sailboat navigating via the Castor star path toward Pelusium and Avaris in ancient Egypt.

360° photograph of Kato Zakro central court and measured orientations.

Crete maintained important trade partnerships in the east, including with Sidon and Byblos (both in present-day Lebanon), Tel Kabri (in modern Israel), Tell el-Dab’a (Egypt), and other key locations. Evidence of Minoan artifacts and murals has been found in many of these places.

Map of proposed star path orientations from Crete to the Near East.

Map of proposed star path orientations from Crete to the Near East.

Minoan elites: wealth, knowledge, and trading by starlight

Connections with the east mattered to the elites of Bronze Age Crete. The eastward orientation of Minoan palaces symbolized elite influence in foreign trade. Wealthy Minoans likely monopolized long-distance trade (and the profits made from exporting Crete’s wine and oils).

Just as the uber-wealthy of the 21st century flaunt their Birkin bags and Rolex watches, Bronze Age elites exhibited their wealth through prestige goods, such as ivory and gold, which came from abroad.

Minoan elites may have protected their trade networks by gatekeeping the knowledge of celestial navigation. Studies in the 1990s showed that the Minoans had knowledge of night sailing and further work in 2013 by Thomas Tartaron suggested that the elites kept the knowledge of using stars for navigation a secret (like the chief navigator families of the Pacific). According to Tartaron, maritime knowledge was ‘worth guarding as a potential source of power and independence…those with access to distant places with their exotic products and…knowledge possessed a special, perhaps even mystical status.’

The wealth of Minoan elites would have allowed them to access foreign knowledge, like an incipient trigonometry perhaps used for establishing the orientations of the palaces, as well as develop their own technologies such as the sidereal compass. Used by traditional sailors in the Caroline Islands of Micronesia, the sidereal compass, known from at least the 9th century in the Indian Ocean, could determine the directions to specific islands based on star paths, which were marked as points analogous to a mariner’s compass. It’s possible existence in the Bronze Age highlights the sophisticated understanding of navigation that existed at this time.

A new study looks to Crete’s palaces for answers

The problem often facing classical and ancient scholars – that is, the lack of written evidence – makes an appearance here. But the lack of written evidence from Crete can be partially overcome. The comparative study of Polynesian and Micronesian sea-faring can point to possible techniques used by the Minoans, for example, the Polynesian practice of observing star paths for navigation or even the use of the sidereal compass.

The recent study by Alessandro Berio used ancient sea routes, software simulations of ancient skies, archaeological records, and wind patterns to highlight the link between Minoan palaces and sea-faring techniques.

A key example was the orientation of the palace of Knossos – the largest Minoan palace in Crete and home to the legendary King Minos. This important palace was oriented toward the star Spica – the movement of which would have helped navigators sail to the important Levantine harbor of Sidon, where evidence of Minoan artifacts has been found. The connection between Crete and Sidon was memorialized on ancient Minoan coins which showed the myth of Zeus turning into a bull and abducting Princess Europa (mother of King Minos) on the beaches of Sidon, from where she was taken to Crete.

Furthermore, Spica’s classical name, originates from the Latin for “spike, ear of wheat” and is associated with the goddess “Šala, the ear of grain” in Babylonian mythology. The study points to the fact that the Linear A word KU-NI-SU has been speculated to mean “a type of grain or wheat,” and be the etymological root for the toponym “Knossos”. This translation would coincide with the alignment of Knossos toward Spica, and may provide further clues about the undeciphered Linear A.

Satellite photo of the Minoan Knossos palace showing the short axis of the central court pointing along the star path of Spica toward the ancient trade harbor of Sidon, location where Minos’s mother Europa was abducted.

Comprehending the importance of stars for navigation brings us a step closer to understanding the Minoan civilization and its role in the ancient world. By looking to the stars, the new study shows us the island’s centrality in the Bronze Age economic and cultural landscape and the importance of trade in shaping Crete’s palaces.

According to the researcher Alessandro Berio, ‘a sophisticated maritime culture’ existed and the study showed that the Minoans ‘relied on long-distance sea voyages for trade’. These findings offer a better understanding of ancient culture and connections in the Bronze Age Mediterranean.